Rx Alert – October 2014

The drug marketplace is constantly changing,  and new prescription drugs are continually entering the marketplace.

and new prescription drugs are continually entering the marketplace.

To protect your plan beneficiaries’ health – and your Plan’s financial resources – your Plan needs to position itself to monitor – and respond – to all these new drug developments.

You may assume that your Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM) is carefully evaluating all new drugs and implementing effective Step Therapy, Prior Authorization and Quantity Limit Programs. But your PBM may instead be “chasing rebates” and favoring new, high-cost drugs to obtain increased rebates that will win new clients in PBM RFPs.

Therefore, to protect your plan beneficiaries’ health as well as your plan assets, your Plan should consider customizing your Formulary – and your various Programs – as well as excluding many newly approved drugs from your Formulary until better evidence becomes available about the drugs’ efficacy and safety.

Are Your Plan Beneficiaries Part of the Next Post-Approval Study?

Since the beginning of this year, the FDA has issued more than two dozen new drug approvals. For Type 2 diabetes, the FDA approved 4 new treatments in 2014: Farxiga (in January), Tanzeum (in April), Jardiance (in August) and Trulicity (in September). Those approvals followed 4 new diabetes drug approvals in 2013 – for Invokana, Nesina, Kazano and Oseni.

It’s reasonably certain that hundreds – or  thousands – of your plan beneficiaries are already taking these new drugs. Turn on your TV and you’ll be bombarded by advertisements for some of these drugs. Moreover, manufacturer drug reps have already fanned out across the country to doctors’ offices encouraging doctors to prescribe these new drugs.

thousands – of your plan beneficiaries are already taking these new drugs. Turn on your TV and you’ll be bombarded by advertisements for some of these drugs. Moreover, manufacturer drug reps have already fanned out across the country to doctors’ offices encouraging doctors to prescribe these new drugs.

But is it wise medically – or financially – for your plan beneficiaries to be using these new drugs?

Weaknesses In The FDA’s Approval Process

When a new drug is approved, typically it’s been tested on approximately 600 to 3,000 people. That’s not enough people to detect problems that may develop when far more people take the drug.

The tested individuals are also typically monitored for a very short period of time, usually ranging from as little as a few weeks to periods of several months. That’s not a long enough period to determine what will happen when people take the drug for many months or years.

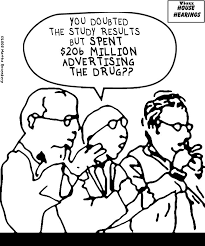

Also, the drug is typically tested only against a placebo, not head-to-head against other drugs that are already on the market to treat the same condition. Therefore, typically, no one knows whether the drug offers any real benefit over existing drugs.

Even more important, there’s often doubt about the scientific evidence of the drug’s effectiveness and safety. It’s true that at the end of its testing, the drug manufacturer must submit to the FDA all clinical trials that the manufacturer conducted. However, if at least two clinical trials of all those submitted show that the drug has some benefit – for some people – that does not result from the placebo – and the drug’s risks do not outweigh that particular benefit – the FDA approves the drug and allows its manufacturer to market the drug in the United States.

The above means that if a manufacturer submits 10 clinical trials, and 8 show the drug isn’t effective and 2 show it is, the FDA will conclude the manufacturer has provided “substantial evidence” of the drug’s efficacy, and the FDA will approve the drug. And with many new drugs, that’s exactly what happens!

In sum, given the limited number of people tested – the short time period over which they were tested – and the relatively weak standard for approval, when a drug is approved typically we have no knowledge of: (i) what will happen when hundreds of thousands or millions of people take the drug; (ii) what effects the drug may have when taken over long periods; (iii) whether the drug is better than existing drugs; (iv) or whether the drug is effective or safe at all. We also typically know nothing about drug-to-drug interactions, since drugs are tested on individuals who are not taking other drugs.

Post-Approval Drug Withdrawals, Black Box Warnings & Adverse Drug Reactions

Tellingly, during the past 4 decades, more than 130 drugs that the FDA approved were subsequently withdrawn from the market because they were deemed unsafe and often lethal.

From 1975 to 2000, 8.2% of FDA-approved drugs subsequently acquired the FDA’s strongest of warnings – a “Black Box Warning.” A recent study showed that since 1996, of 522 novel drugs approved, about one-third required boxed warnings, with many of those warnings issued after approval. The median time from approval to first boxed warning was 4.2 years.

It’s also worth noting that drugs rarely are withdrawn – or given Black Box Warnings – as soon as safety issues arise. Quite the contrary.

As FDA scientist Dr. David Graham warned when testifying before a Senate Committee, “the scientific standards [that the FDA] applies to drug safety guarantee that unsafe and deadly drugs will remain on the US market.” Dr. Graham went on to explain:

“When it comes to safety, the … paradigm of 95% certainty prevails. Under this paradigm, a drug is safe until you can show with 95% or greater certainty that it is not safe. This is an incredibly high, almost insurmountable barrier to overcome. It’s the equivalent of ‘beyond a shadow of a doubt.’ And here’s an added kicker. In order to demonstrate a safety problem with 95% certainty, extremely large studies are often needed. And guess what. Those large studies can’t be done.”

Thus, it’s not at all surprising that every year, there are about 2 million adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and about 100,000 ADR-related deaths.

Your Plan’s diligence in monitoring – and responding to – new drugs may protect one of your plan beneficiaries from becoming one of those statistics.

The Benefit Of “The Known” Clearly Trumps The Risk Of “The Unknown”

All of the above facts mean that unless a new drug is a “break-through” drug, the health of your plan beneficiaries is likely to be far better protected if they avoid new drugs and rely on existing drugs that have withstood the test of time. Dr. Sidney Wolfe of Ralph Nader’s Worst Pills, Best Pills newsletter has long labeled most new drugs as “Do Not Use” drugs. Many other experts support his view, including the highly-regarded Consumer Reports on Health.

For diabetes control, experts agree that there are several tried-and-true generic drugs that your plan beneficiaries should first be encouraged to use, including metformin and the 3 sulfonylureas: glyburide, glimepiride and glipizide. That means, your Plan should make sure your PBM has implemented Step Therapy or Prior Authorization Programs related to all the new diabetes treatments.

Some PBMs have done so for some clients. Do you know what your PBM has done for your Plan?

And are you positioned to ensure that your PBM will react carefully and quickly to the next new drug that enters the marketplace?

Controlling Drug Use Reduces Plan Costs

It’s also worth noting that older, generic drugs are almost always far less expensive than new brand drugs. For diabetes control, metformin and the sulfonylureas should cost your Plan somewhere between $4 and about $50 per 30 day prescription (assuming your PBM contract contains reasonable price controls). In contrast, each of the new drugs is likely to cost your Plan several hundred dollars per 30 day treatment.

Looked at in a different way, the AWP of metformin ranges from 70 cents to $1.44 per unit (depending on the dosage level). For Jardiance, the AWP is $12.04 per unit, and for Invokana and Farxiga it’s $12.48.

Which cost does it make sense for your Plan to incur, if there’s no evidence that the more expensive new drugs are any better therapeutically than metformin, and their risk profiles are largely unknown?

Conclusion

According to a study comparing 2013 and 2012 costs for diabetes treatments, our nation spent 14% more on diabetes drugs in 2013 than in 2012. A major cause of the increase was the use of the 4 new high-cost drugs that were approved in 2013.

Do your know how many of your Plan Beneficiaries used those 4 drugs in 2013? Do you know the impact of those drugs on your Plan’s bottom line? And do you know what your PBM did to protect your plan beneficiaries – and your Plan – from such use?

Even more important, what has your PBM done to respond to the FDA’s approval of 4 new diabetes treatments this year?

In short, there are strong reasons for your Plan to consider customizing your Formulary – and Programs – and blocking many newly approved drugs, until the passage of time has enabled more information to emerge about the drugs’ safety and efficacy. If you don’t have the resources to do so, consider joining a Coalition. Just make sure that the Coalition has a PBM contract in place that allows customization – for every Coalition Member – and also verify that the Coalition is actually performing customization for Coalition Members.

If you’re interested in talking about the work our National Prescription Coverage Coalition is performing, do give us a ring. We’d love to talk with you. Call 973 975-0900.