Most health plans’ prescription coverage programs allow plan beneficiaries to purchase drugs at virtually all retail pharmacies in the United States, regardless of the prices charged by those pharmacies.

Most health plans’ prescription coverage programs allow plan beneficiaries to purchase drugs at virtually all retail pharmacies in the United States, regardless of the prices charged by those pharmacies.

But in a time of out-of-control drug costs, every health plan administrator should be questioning this approach and asking two critical questions:

- How many retail pharmacies are needed in my plan’s pharmacy network to provide sufficient pharmacy access to my plan beneficiaries?

- How much could my health plan save if some – or all – high cost pharmacies were eliminated from – or at least disfavored in – my plan’s retail pharmacy network?

And here’s a final, critically important question for all of us to ask: If more health plans started excluding – or disfavoring – the high-cost pharmacy chains, might we together force those chains to dramatically lower their prices?

Basic Facts About Retail Pharmacies & Their Costs

There are more than 67,000 retail pharmacies in the United States.

The two largest chains – CVS and Walgreens – respectively have more than 9,600 and 8,100 stores each. CVS has recently acquired Target, and Walgreens is likely to soon acquire Rite Aid, which will increase each chain’s size by several thousand more pharmacies.

But notwithstanding the sizes of CVS and Walgreens, there are almost 53,000 other pharmacies in the U.S. available to provide drugs to your beneficiaries.

Pharmacies’ costs vary enormously, including for health plans paying for drugs through PBMs or insurance companies.That’s because when PBMs and insurers enter into contracts with pharmacies, PBMs’ and insurers’ bargaining power differs depending on the pharmacy’s size:

CVS and Walgreens are so large that they can – and do – demand high reimbursement rates. Certain other chain pharmacies – like Walmart, Costco, Winn-Dixie and Publix – could demand high reimbursements too, but don’t. As a result, those chains provide drugs at far lower costs than CVS or Walgreens.

Also notable: Most independent pharmacies are without any leverage to demand anything from any PBM or insurer and therefore accept the reimbursement terms dictated by PBMs and insurers. The exception to this general rule: Independent pharmacies in isolated rural areas are needed to ensure sufficient access in the rural areas and can therefore insist on higher reimbursements.

Given all the above facts, assuming your health plan has contracted to obtain retail pharmacy pass-through pricing, the cost that your health plan is paying for any particular drug will vary enormously, depending on the pharmacy where the drug is purchased.

How Much Do Pharmacies’ Costs Differ?

Our consulting firm – and Coalition – regularly analyze the costs of different pharmacies for our clients.

We consistently find that drugs – particularly generic drugs – are far more expensive at CVS and Walgreens than at other pharmacies. The costs at Walmart, Costco, Winn-Dixie and Publix are consistently far lower, as are the costs of most independent pharmacies.

In fact, the average generic AWP discount provided by CVS and Walgreens is often in the low 70s (or worse). That’s often even true, when the PBM is Caremark, and the client’s contract with Caremark purportedly provides lower-costs from CVS pharmacies.

In contrast, Walmart, Costco, Winn-Dixie and Publix often provide average generic discounts of AWP-79% (or better), as do many independents and other small chains.

Note that this means that the cost of generic drugs, on average, are about 50% higher at CVS and Walgreens than at the lower-cost pharmacies!

The above facts mean that there is always money to be saved, if health plans can ensure fewer prescriptions are filled at CVS and Walgreens.

How much will actually be saved depends on many factors, including: the size of the health plan, the percentage of beneficiaries using the high-cost pharmacies, and how many beneficiaries change their purchasing venues. But regardless, a considerable sum of money will likely be saved if health plans take action to address the high costs charged by CVS and Walgreens.

Are CVS & Walgreens Needed To Provide Sufficient Access?

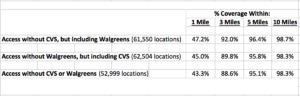

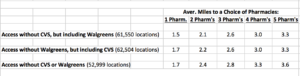

Our consulting firm – and Coalition – also conduct geo-access studies for our clients to determine the impact on beneficiaries’ pharmacy access if certain pharmacies are excluded from a client’s network.

Either CVS – or Walgreens – can almost always be eliminated from a pharmacy network, and beneficiaries will still have remarkable access to a pharmacy within a short distance of their homes.

More striking, both CVS and Walgreens can be excluded from pharmacy networks, and beneficiaries’ pharmacy access will still be very strong, assuming a health plans’ beneficiaries are located largely in metropolitan areas.

For example, a recent analysis of one client’s data showed that more than 95% of beneficiaries in a metropolitan area (without subways) would have access to a pharmacy within 5 miles, even if all CVS and Walgreens pharmacies were excluded from the client’s pharmacy network:

Tellingly, those savings occurred without any cost shifting from the Plan to plan beneficiaries, and without changing beneficiaries’ access to any drugs. The savings were solely the result of excluding the two high-cost chains and requiring beneficiaries to use other lower-cost pharmacies. Thus, slightly decreasing the size of your pharmacy network may be a relatively pain-free method of achieving dramatic savings.

Note too: Armed with facts like those described above, health plans can ask each chain if it will significantly reduce its costs, if the other chain is excluded.

Based on our firm’s experience, it’s possible that both chains will offer to do so. Also based on our firm’s experience, it’s possible that at least one chain will offer such steep discounts that the health plan will save even more by retaining that chain in the network, and only removing the less-competitive chain. Thus, health plans can force these two high-cost pharmacy chains to compete against each other to retain clientele.

And isn’t that exactly the result that all of us should be seeking: Drastically lower costs brought about by health plans exercising their market power?

An Alternative: Give Beneficiaries the Right To Choose Lower-Cost Pharmacies

When health plans exclude pharmacies from their network, they are creating what’s known as a Limited Pharmacy Network. By doing so, they restrict their prescription coverage to lower-cost pharmacies and entirely exclude higher-cost pharmacies.

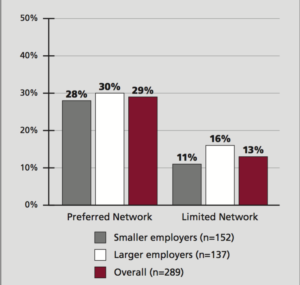

However, health plans can also give beneficiaries a choice of all pharmacies, and try to incentivize their beneficiaries to use lower-cost pharmacies by imposing higher copays at the higher-cost pharmacies. Doing so creates what’s known as a Preferred Pharmacy Network.

The disadvantage of Preferred Networks is that health plans are likely to save far less. Higher copayments may not create a sufficient incentive to change many beneficiaries’ pharmacy choices. That’s particularly true, given beneficiaries’ widespread use of coupons to reduce – or even eliminate – their copayment burden.

Unfortunately, of those health plans that have acted to obtain lower pharmacy costs, more have chosen to implement Preferred Pharmacy Networks than Limited Pharmacy Networks (29% vs. 13%, according to a recent PBMI survey): (1)

Notably, most stand-alone Medicare Part D plans now rely on Preferred Pharmacy Networks: In fact, the “share of Part D stand-alone drug plans with tiered pharmacy networks grew from 7 percent in 2011 to 87 percent in 2015.”(2)

When Creating A Limited – or Preferred – Pharmacy Network, Beware!

To ensure health plan savings, health plans must put in place PBM contracts that require actual retail pass-through pricing. Otherwise, you may incentivize your members to use lower-cost pharmacies, but your PBM may continue to charge you the same steep prices, meaning your PBM (not your plan) will reap the financial benefit of your actions.

PBM contracts must also contain brand/generic/and specialty drug definitions that prevent PBMs from shifting drugs between categories to camouflage drugs’ actual costs at certain pharmacies. Too often, PBMs report their average costs to clients at preferred pharmacies, and the PBMs’ reports are inaccurate.

Clearly, health plans should be particularly careful when their PBMs have relationships with a pharmacy chain. Thus, plans using Caremark should independently scrutinize their claims data to evaluate different pharmacy costs, given Caremark’s relationship with CVS. Prime Therapeutics’ newly-penned deal with Walgreens gives Prime’s clients reason to analyze their claims data as well.

Educate Your Beneficiaries

We believe it’s critically important for every health plan to educate plan beneficiaries about pharmacies’ different costs, and to encourage beneficiaries to use lower-cost pharmacies.

Start by analyzing your claims data to determine your average brand – and average generic – costs at each of the chain pharmacies, as well as at independents. This will arm you with information about the differences in pharmacies’ costs.

Then mount a campaign to urge your beneficiaries to use lower-cost pharmacies, and explain how much your plan will save if your beneficiaries do.

Also, if relevant, tell your beneficiaries how much they are likely to save, if they change their buying habits. The numbers will surprise you – and them! This is particularly true, if your benefit design requires beneficiaries to share in drugs’ costs by imposing deductibles, or by requiring beneficiaries to pay coinsurance rather than copayments (a percentage of drugs’ costs rather than flat amounts).

Most important of all, consider implementing a Limited Pharmacy Network – or at least a Preferred Network – and explain to your beneficiaries why you are doing so, and the savings that will result.

If more Plans take steps to respond to non-competitive drug pricing, we can – and will – change the marketplace.

# # #

To read other Rx Drug Alerts published by our firm, go here.

Footnotes:

(1) PBMI, “2015-2016 Prescription Drug Benefit Cost and Plan Design Report” at p.13 . See http://reports.pbmi.com/report.php?id=13

(2) Jack Hadley, Juliette Cubanski, and Tricia Neuman, “Medicare Part D at Ten Years: The 2015 Marketplace and Key Trends, 2006-2015”. See http://kff.org/medicare/report/medicare-part-d-at-ten-years-the-2015-marketplace-and-key-trends-2006-2015/.